A closer look at a mix of ancient and newly discovered fossils suggests that an ancient species of photosynthetic bacteria was one of the first of its kind to live on dry land more than 400 million years ago.

The properties of the microbe, called Langiella scourfieldii, place it in the class of cyanobacteria that lived and thrived among some of the first plants to grow on Earth, as well as in bodies of fresh water and hot springs, as similar species still do today.

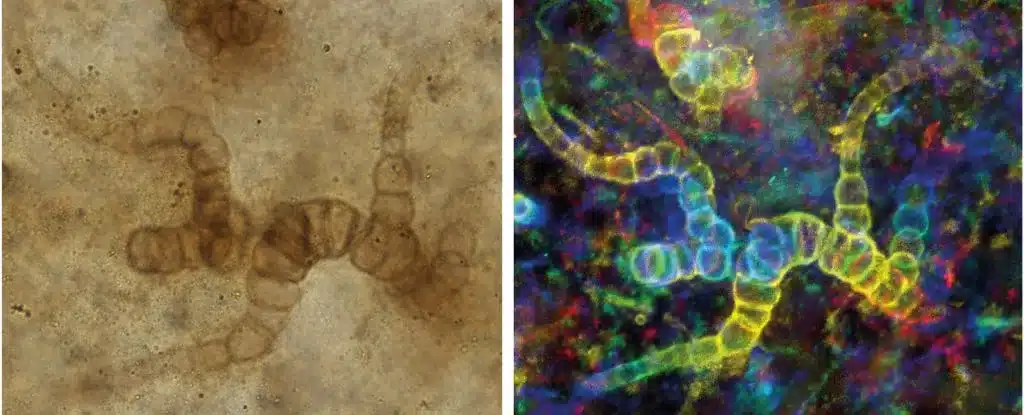

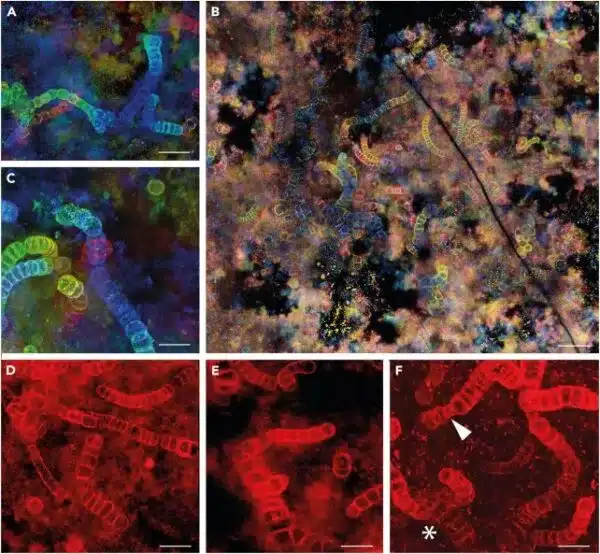

“With the 3D reconstructions, we can see evidence of branching, which is a feature of the cyanobacteria Hapalosiphonacea,” says paleontologist Christine Strollo-Derren of the UK’s National History Museum.

“This is exciting because it means that these are the first cyanobacteria of this type found on Earth.”

The discovery was made in rock chips representing the world’s oldest known preserved terrestrial ecosystem, the Rhynie Rocks in Scotland. Although a diversity of life forms has been identified in fossil strata that are 407 million years old, the role of cyanobacteria is unclear.

Artist’s impression of the Renais flint landscape, 407 million years ago. (Victor Leskik)

Also known as blue-green algae (although they’re not actually algae), cyanobacteria are fascinating things. They are essential for life as we know it today, having played a major role in transforming Earth into the hospitable environment it is today about 2.4 billion years ago. When they began to multiply in Earth’s waters, they filled the air with oxygen in what is known as the Great Oxidation Event.

Whether you consider this a good or bad thing depends on where you are in Earth’s history. From our current happy, oxygen-breathing perspective, that’s great. For all other life forms that adapted to Earth in low-oxygen conditions, it was extremely devastating. Devastating mass extinction levels.

But cyanobacteria, which today can be found thriving all over the world, didn’t care. Photosynthetic microbes persisted, inserting themselves into whatever environmental conditions took them.

Confocal images of Langiella scourfieldii, with false color to show depth. (Strollo-Deren et al., iScience, 2023)

Because they are thought to have originated in freshwater environments, cyanobacteria are presumed to have transitioned from waterlogged conditions to life on land quite easily and early.

But it’s hard to know how he got a place for himself. The new findings are an important piece of the puzzle.

“Cyanobacteria in the Early Devonian played the same role they do today,” Strollo-Deren says.

“Some organisms use them for food, but they are also important for photosynthesis. We knew they were already there when plants began to colonize the land and perhaps competed with them for space.”

Langiella scourfieldii was first discovered in 1959, but it was difficult to distinguish between specimens. But since then, additional specimens have been discovered, allowing researchers to investigate further.

They used super-resolution microscopy and 3D reconstruction on new specimens of Langiella scourfieldii to find out how they grow.

Cyanobacteria are responsible for blooms like this almost every year in the Baltic Sea and elsewhere around the world. (NASA Earth Observatory)

They found evidence of a structural feature known as true branching, which occurs when bacteria growing together in one line sometimes multiply, causing another line to branch. The team says this represents evidence that bacteria were inhabiting the wetland surrounding the hot springs.

Combined with other evidence, such as molecular clock analyses, and specimens like a billion-year-old branching specimen discovered in Africa a few years ago, the results suggest that cyanobacteria have a much more complex evolutionary history than that preserved in the fossil record, the researchers say.

“Despite the emergence of embryonic plants as competitors for space, nutrients, and novel structural elements in ecosystems of increasing spatial complexity, cyanobacteria continued to thrive in both Rainy Hot Springs and adjacent wetlands, as they do today in similar terrestrial environments,” they wrote. .

“Able to colonize rapidly, Nostocalean cyanobacteria flourished on surfaces inundated with sedimentary plant debris.”

Translated by Matthews Lineker from Science Alert

“Friendly zombie guru. Avid pop culture scholar. Freelance travel geek. Wannabe troublemaker. Coffee specialist.”