:strip_icc()/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_59edd422c0c84a879bd37670ae4f538a/internal_photos/bs/2021/3/K/mkA8i9Si29R6eWqT6S0Q/rfi.jpg)

Cape Verdeans go to the polls on Sunday (17) to choose the country’s next president. Seven candidates are vying for the position currently held by Jorge Carlos Fonseca, who left the position after two terms.

While many countries in the region face coups or leaders who do everything to stay in power, the small Portuguese-speaking archipelago is seen as a model for democratic stability in the African region.

About 400,000 voters were called to participate in the elections, which are disputed between Fernando Rocha Delgado, Gelson Alves, Jose Maria Neves, Carlos Vega, Helio Sanchez, Casemiro de Pena and Joaquim Monteiro.

Unlike its neighbors, Cape Verde is ranked as one of the best African countries in terms of governance.

The former Portuguese colony, independent since 1975, lived under the one-party system until 1990, when the first democratic elections were held. Since then, Cape Verdeans have been living under a politically stable system, in which the executive power is controlled by the prime minister.

The current president, who has been in power since 2011, cannot try to delegate him for a third term. In addition, the elected candidate has only a representative role abroad, in addition to appointing the head of government according to the results of the legislative elections.

“We are a small archipelago with a small population. Sociologist Roselma Evora sums up our tradition of civil governments, in order to explain political stability in Cape Verde, in a region where political transitions do not always occur in a peaceful manner.

He adds, “We also have a constitutional formation for the separation of powers with a parliamentary system,” noting that even if the head of state can veto the enactment of a law and is the commander of the armed forces, the primary power is concentrated in the hands of the prime minister.

Formation can affect turnout, with voters not stimulated by presidential elections. “I’m not voting because it wouldn’t change my life at all, which is why I chose not to vote,” said Adilson, a Cape Verdean designer whose voice was heard on the streets of Praia.

Recalling the health context, he said, “If you have to wait in line and run the risk of infection, I think it’s not safe because there are so many people who are going to vote and without control.”

Political stability but economic instability

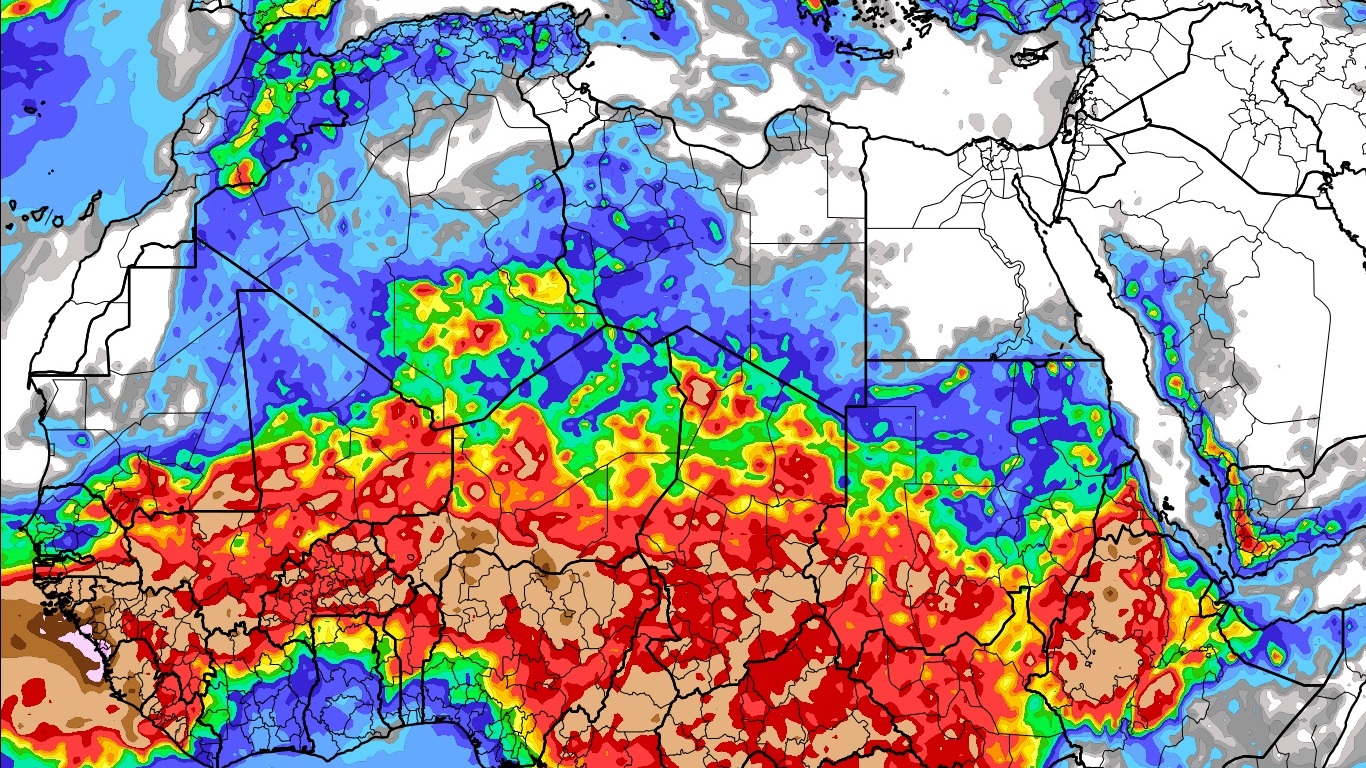

In addition to affecting voters’ motivation to go to the polls, the pandemic has also transformed the country’s economy. Because despite its relative political stability, Cape Verde depends on tourism, which accounts for 25% of its GDP. And Covid-19 ended up shaking Cape Verde’s finances.

In 2019, the archipelago received 800,000 tourists. But in 2020, after years of growth (5.7%, 2019 and 4.5% in 2018), Cape Verde recorded a drop in visitors, followed by a historic recession of about 14%. Most of the hotels closed and many Cape Verdeans, who worked in this sector, lost their jobs.

In addition, Cape Verde imports 90% of what it consumes, in part because of its volcanic topography, with only 10% of its arable land, creating a certain economic vulnerability. Diaspora remittances also account for 14% of GDP according to the World Bank.

Videos: G1 most viewed in the last 7 days

“Proud explorer. Freelance social media expert. Problem solver. Gamer.”