With more than 650,000 potential cases of dengue reported by the Ministry of Health, Brazil is on alert in anticipation of an outbreak, driven in particular by notifications in the Federal District, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. Ciara takes issue with that reality: According to state health department data, case reporting has practically dropped by half this year compared to last.

The state recorded 2,047 possible cases of dengue fever this year, while last year it recorded 3,234 cases in the same period. 266 cases have been confirmed so far. Last year, there were 575 in January and February.

According to experts and managers, the state's historical coexistence with the disease, the fact that it has a lower proportion of the population exposed to the serotypes circulating in the country, and the delayed onset of the rainy season, are some of the reasons that explain the low infection rate. The disease occurred at the beginning of this year.

“Ceara is going against the grain because it has been within reach for so long,” says Antonio Lima Neto, executive secretary for health surveillance at Ceará's health department, Antonio Lima Neto, known as Tanta. The state has seen at least seven dengue epidemics in the past 40 years, and according to the director, the state has a kind of “immune barrier” against some serotypes of the disease.

Dengue infection is caused by four serotypes prevalent in the Americas: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4. The species currently most traded in Brazil are 1 and 2, the same species that have already been widespread in the municipalities of Ceará in recent years. Because Ceará and other states in the northeast have a history of epidemics, Tanta believes that the proportion of the population vulnerable to the disease will be lower than in the states of the southeast and south, which have begun to encounter the disease more recently, with larger populations. Associated with high prevalence, climate emergencies, and heavy rainfall.

The situation in Ceará seems more comfortable than in other parts of the country, but expert managers agree that we cannot let our guard down against mosquitoes. This is because another factor that may explain the state's lower infection rate is the delayed start of the rainy season, when there is usually greater accumulation of water, and thus greater spread. Aedes aegypti. The peak of dengue fever in Ceará is usually between April and May.

“The rainy season started later,” says Magda Almeida, professor at the Department of Community Health at the Federal University of Ceara. “We may see, from now on, an increase in arboviruses, such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika.” The low infection rate in the first months is encouraging.

Tanta realizes that the risk of an increase in cases cannot be ruled out, but she claims that this is unlikely. He explains that the Secretariat is developing a surveillance scheme, which includes moving average data from historical series of dengue cases. From there, a statistical upper bound is calculated. “When you are below average, it means you are in a period of low transmission, which is what is happening now,” he explains.

According to him, although the disease usually peaks in April, in outbreak years, the first months already indicated an increase. Be that as it may, the director himself admits that the situation may change if DENV-3 or DENV-4, for example, return to Ceará. Although it is rare to see two epidemics in consecutive years, the state did so in 2011 and 2012 with DENV-1 being replaced by DENV-4. “If you don't have serotype rotation, the population is vulnerable [no Ceará] “It's much lower than in some states,” he says.

Lessons from epidemics

According to experts, lessons learned from epidemics in recent decades also contribute to controlling cases of infection, especially preventing deaths. One of them is clinical management: informing the population so that they know how to recognize warning signs of disease severity (such as nausea, dizziness, vomiting, abdominal pain) and organize the health system to respond to them in a timely manner. way.compository.

“If I treat this person at this point with saline, I save 99% of cases,” explains infectious diseases doctor and coordinator of the Center for Tropical Medicine at the Federal University of Ceara, Ivo Castelo Branco.

The other lesson, according to Minister Tanta, is to learn not to underestimate the disease's ability to cause an epidemic explosion, and to work to stop transmission when observing an increase in mosquito infection rates (LIRA, which is done by taking samples from household visits), before the data reflects disease cases.

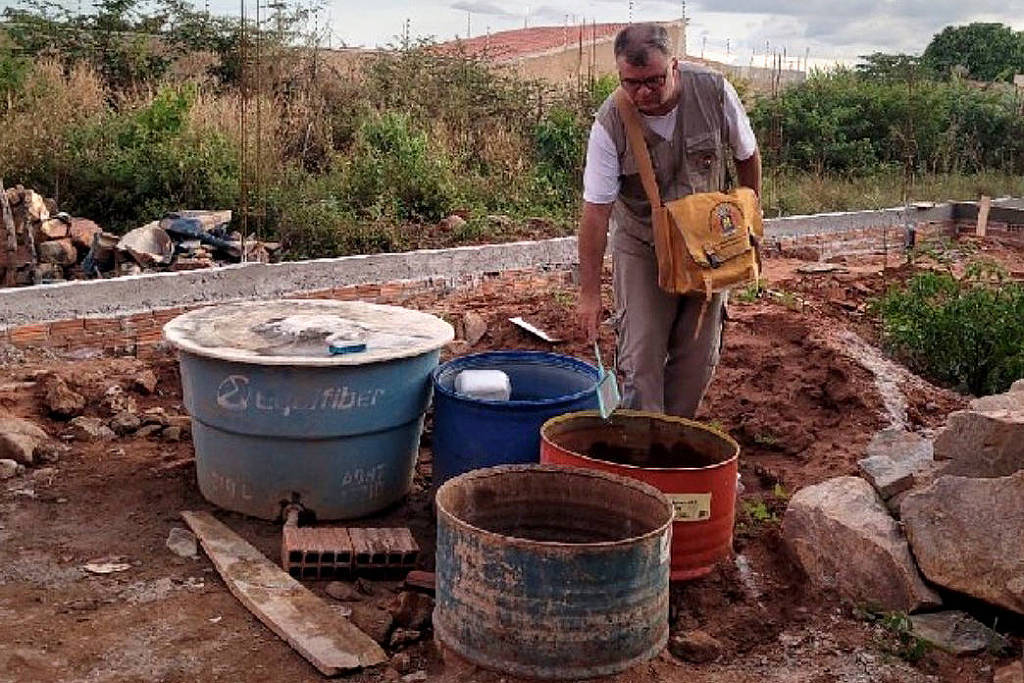

Having an active and vigilant surveillance team and knowledgeable residents to eliminate mosquito infestations at home is another important lesson. “We have had a culture of individual accountability for some time,” says Magda Almeida. In fact, outbreaks vary from region to region, and mosquitoes may breed in trash, in plastic bottles, but also in open water tanks.

“Friendly zombie guru. Avid pop culture scholar. Freelance travel geek. Wannabe troublemaker. Coffee specialist.”