A recently published paper used drawings made by astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) in 1607 to better understand and document the dynamics of solar cycles. The conclusion, which calls into question an assumption previously made by other scientists, remains inconclusive—Kepler’s records alone, which were analyzed in the study, are not enough.

Periodically, the Sun undergoes changes in its degree of activity. Such changes typically occur every 11 years, starting from what experts call a minimum to a maximum and then back to a minimum – and these dynamics consist of solar cycles.

During these variations, sunspots appear at different locations on the star's surface. At the beginning of the cycle, for example, they tend to be located at the highest latitudes of the Sun, and then later move toward more central regions of the star.

These spots mainly provide information about the Sun, explains Hisashi Hayakawa, of the Space and Earth Environment Research Institute at Nagoya University in Japan: “However, solar activity can also affect terrestrial environments. Therefore, such studies could also have some implications for Earth,” adds Hayakawa, who is one of the book’s authors. condition Recently published in the scientific journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

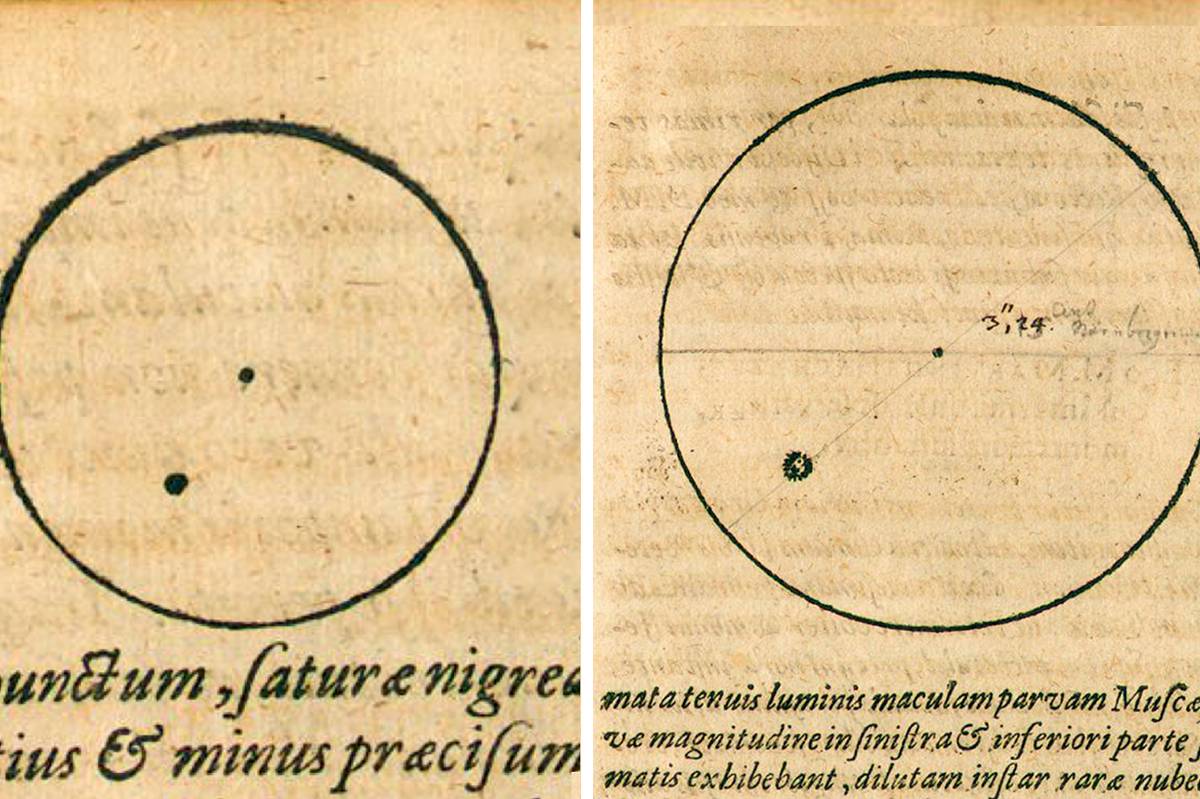

What Hayakawa and other researchers who signed the text are arguing is that the records made by Kepler, one of the most important figures in science, were of sunspots. Such drawings could only have been made using the camera obscura technique.

“This method consists of a pinhole and a dark room to view external images, including the solar disk,” Hayakawa explains. Although it allows for a view of the sun’s surface, a camera is not the most recommended alternative for this purpose. “They have difficulty capturing smaller sunspots than telescopes,” Hayakawa continues.

However, the researchers used Kepler's drawings as well as mathematical calculations to estimate the location of the spots the scientist had recorded on the solar surface. The conclusion was that these spots were not found at the highest latitudes of the sun, an indication that they corresponded to the end of the solar cycle.

Therefore, the authors suggest that Kepler's 1607 drawings may be the result of the end of a solar cycle called -14. On the other hand, records from 1610 show sunspots at higher latitudes, an indication that it will be the start of another solar cycle – in this case, called -13.

The study’s finding is significant because there is no evidence for Solar Cycle 14. Therefore, experts believe that Cycle 13 is an anomaly in its duration, not in line with the standard 11-year average. In the paper, the authors refute this point, arguing that “the Sun was probably just doing its daily thing, not something special,” Hayakawa concludes.

But the research is preliminary. In addition to the fact that the camera obscura is not the best way to record sunspots, Hayakawa notes that Kepler’s records are the only ones that exist, at least for now. “Ideally, we need more sunspot records from the early 17th century to make this conclusion more robust,” he concludes.