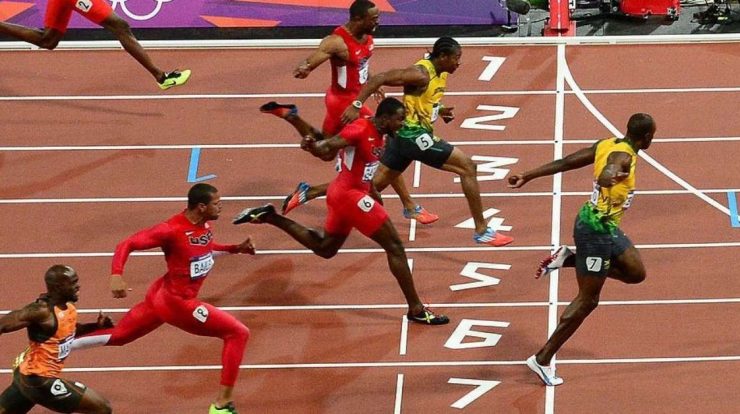

There was an earthquake at the world’s premier athletics event, but spectators at London’s Olympic Stadium for the 2012 Olympics may not have noticed.

Understandably, they were distracted by the sight of Usain Bolt flying across the finish line in the men’s 100m.

The Jamaican star won another gold medal that night and set an Olympic record of 9.63 seconds.

“It was one of the best races of all time,” explains Steve Hack, professor of sports engineering at Sheffield Hallam University in the UK.

But Hack doesn’t just praise Bolt. His comment is driven by the overall performance of the peloton: seven of the eight athletes who participated in that final crossed the line in less than 10 seconds – an unprecedented.

The 10-second barrier was first broken in 1968, and it continues to be a remarkable achievement for runners: a badge of honor that sets them apart from their peers.

But the number of under-10 runners has grown in recent years.

Data from World Athletics (formerly IAAF), the sport’s governing body, shows that in the four decades between 1968 and 2008, only 67 athletes managed to break the barrier. Another 70 will join the club over the next 10 years.

And in the past two years, through early July 2021, another 17 men have had their first days under 10. The equivalent barrier for women – 11 seconds – is also being broken more and more.

What is happening?

club expansion

Scientists like Haake believe in a combination of factors, starting with increased participation in track events around the world. Then comes the access to better training methods.

“More athletes around the world are now taking advantage of elite training and the help of sports science and technology to improve their chances of running faster,” Hack adds.

The proof is that the Under-10 Club has expanded beyond the usual powers of the United States, Jamaica, Great Britain and Canada – all countries that have won at least one Olympic gold medal in the men’s 100m.

Nigeria, for example, shares with Great Britain the third-highest number of athletes to break the 10-second barrier, with 10, while recent additions to the club include Japan, Turkey, China and South Africa, countries less known for their running excellence. .

Similar results also occurred in the women’s 100m. The 11-second barrier was first broken in 1973 by East German sprinter Renate Stiecher. In 2011, 67 other athletes also performed this feat. Ten years later, the total is 115 and also includes countries with fewer traditions in the event.

Footwear, athletics and sports science

The technology has really come in handy: runners these days run with lighter shoes – newer models can weigh less than 150 grams.

Shoes today are also made of radically different materials. One example is the collaboration between German shoe maker Puma and the Mercedes Formula 1 team, which resulted in running shoes with a carbon fiber sole – the same material used in world champion Lewis Hamilton’s car.

Racetracks have come a long way since the days when top athletes would run on cobbled or grass surfaces in competition.

Synthetic tracks debuted at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico, providing more protection for athletes’ joints and promising a springboard effect that would lead to faster times.

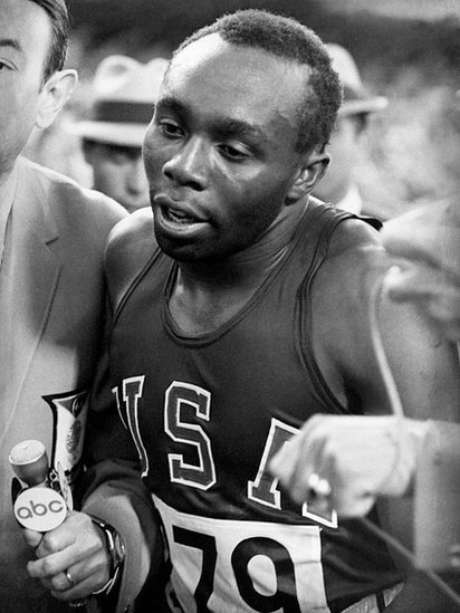

At those same Games, American sprinter Jim Hines became the first man to run the 100 meters in less than 10 seconds, finishing in 9.95 seconds.

The craving for “faster” trails means the shape of the vulcanized rubber granules used to build the running surface is now taken into account.

At the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Italian surface maker Mondo celebrated five world records on the track that it provided to the athletic competition almost as well as runners.

Science has also played an important role in nutrition and training. Runners these days can be examined and adjustments made to technique and reaction times.

Research has identified even the most important muscles for runners’ success.

Last October, a team of scientists at Loughborough University, a leading institution in sports science studies, discovered that the gluteus maximus (one of the muscles that makes up the buttock area) is the key to athletes reaching top speed on the track.

“We now know that there is a very specific distribution of muscle in elite runners,” said Sam Allen, a biomechanical specialist who was involved in the research.

“So we’ll soon be able to see runners working specifically on this development.”

Is the barrier psychic too?

In an interview with Japan’s The Asahi Shimbun newspaper on July 9, local sprinter Ryota Yamagata did not hesitate to attribute the under-10 100m race he achieved a month earlier to “the work of scientists over the past 20 years.”

No Japanese sprinter had broken the 10-second barrier until 2017. Since then, Yamagata and three other countrymen have done so.

It also appears that the expansion in terms of number and diversity of the U-10 category makes the barrier less intimidating for athletes.

This is the opinion of China’s Bingtian Su, who in 2015 became the first Asian to run 100 meters in less than 10 seconds.

“I think the barrier is more psychological than physical,” he said in 2019.

Mastering Medals

Obviously, these developments are not an automatic guarantee of success in overcoming the barrier.

So far, for example, many countries, including India, and even an entire continent (South America – including Brazil) still have to produce an under-10 in the men’s 100m or an under-11 sprinter in the women’s race.

In fact, the expansion of the “U10 Club” has not changed the competitive balance when it comes to medals.

In both the men’s and women’s competitions, American and Jamaican runners have consistently dominated the podiums in the Olympic and World Championships since the 1980s.

In the men’s event, for example, the last men’s sprinter outside of these countries to win Olympic gold was Canada’s Donovan Bailey, at the 1996 Atlanta Games.

In the women’s event, Yulia Nestyarinka’s victory at the 2004 Athens Games was a surprise even for the Belarusian, since athletes from the United States had won the race at the five previous Olympics – Jamaicans won the next three.

Things aren’t likely to change at the Tokyo Games, despite being the first after Bolt’s retirement: American sprinters have 4 of the 5 fastest times in the men’s 100m in 2021, while 3 Jamaicans and one American are among the women’s top 5. Planet This planet is general yet.