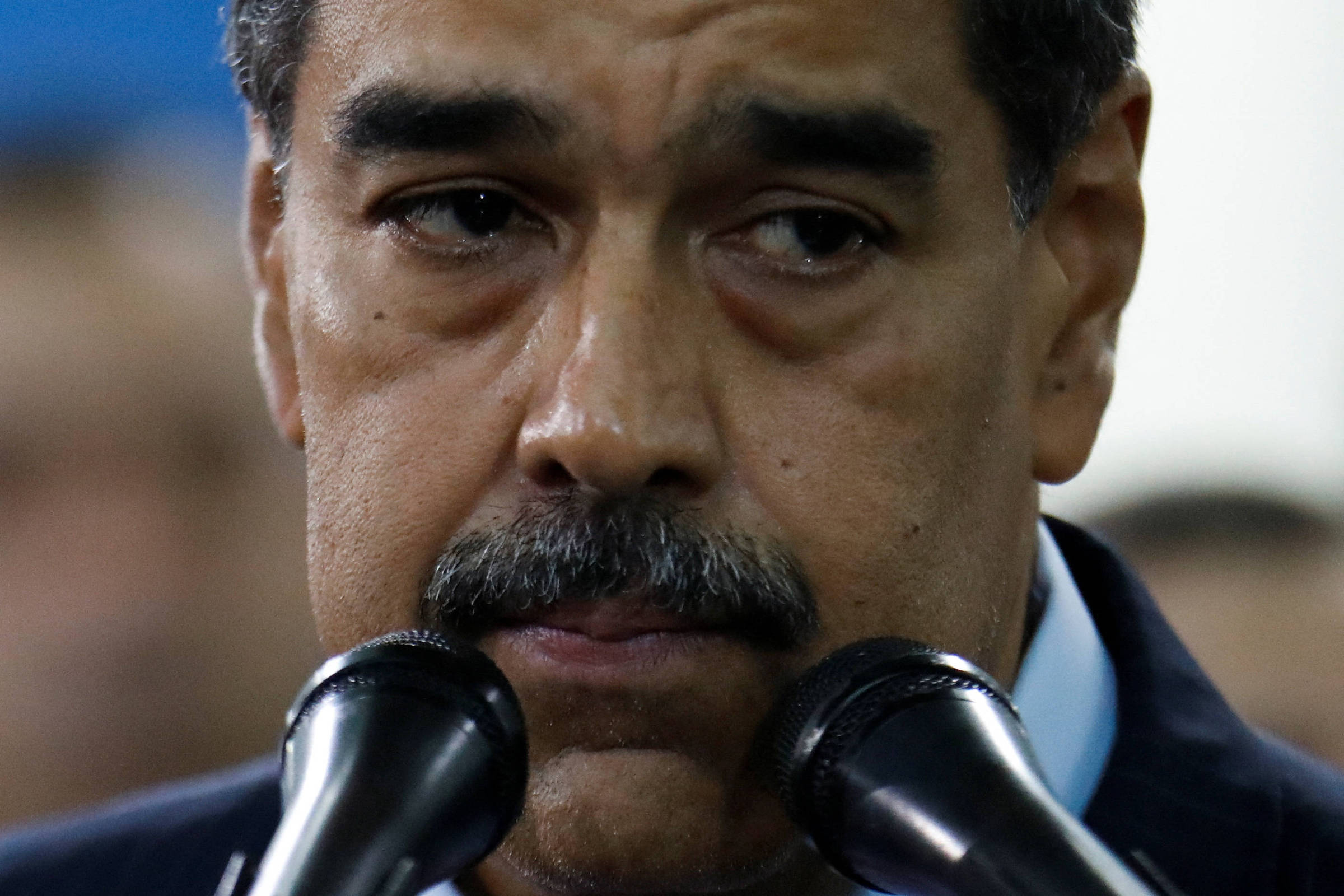

Life is hard for dictators. Suggested by British magazine The Economist Offering Nicolás Maduro political asylum so he can leave power without causing a bloodbath, while it makes sense in theory, may not be easy to implement.

The main reason for this is that dictators cannot trust democracies. Suppose that, following the weekly recommendations, Lula’s government grants Maduro asylum. The Venezuelan may do well at first, enjoying a luxurious retirement, but he will have to live in mistrust forever.

What happens if the political winds change in Brazil, which is common in democracies? Will the election of a right-wing government mean the end of asylum and extradition?

Alternation is not the only danger. Democracies also feature a division of powers.

The judiciary does not necessarily follow the political decision of the executive to grant asylum. If the judges understand that the human rights violations committed by the former dictator constitute crimes against humanity, political asylum will not be granted, under the provisions of the 1998 Rome Statute.

Since former dictators cannot trust democratic systems, can they rely on other authoritarian regimes when negotiating a golden exile? At first glance, yes. After all, what distinguishes a dictatorship is that the dictator’s word is law. No judge will excommunicate you. It is also unusual for dictatorships to encourage fair elections that allow for the transfer of power. The Venezuelan crisis is precisely the result of an attempt to rig the election.

But in a second analysis—and there is another paradox—former dictators cannot trust other authoritarian regimes much, for the simple reason that they are inherently unstable, as Venezuela itself shows.

Tragically, the least uncertain path for dictators is to never give up power and always double down.

Current link: Did you like this text? Subscribers can get seven free accesses from any link daily. Just click the blue F below.

“Proud explorer. Freelance social media expert. Problem solver. Gamer.”