For 16 years, Mogi das Cruzis, a thoracic surgeon and pulmonologist, Olafo Ribeiro Rodriguez, 72, has voluntarily helped Brazilian patients living in Japan return to Brazil to treat various types of ailments. But with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, work that is no longer simple has become more complex.

The conditions that the doctor helps are patients with cancer, the need for an organ transplant, stroke, kidney disease, advanced diabetes, and other conditions that require agility in treatment. The choice is to have the patient treated in Brazil.

In 16 years working as a volunteer for an NGO helping sick Brazilians return to the country, Rodriguez has already brought more than 30 patients. “Most of them are from Sao Paulo, but they really brought people from Londrina, Marenga and Cascavel in Parana, Pernambuco and Mato Grosso.”

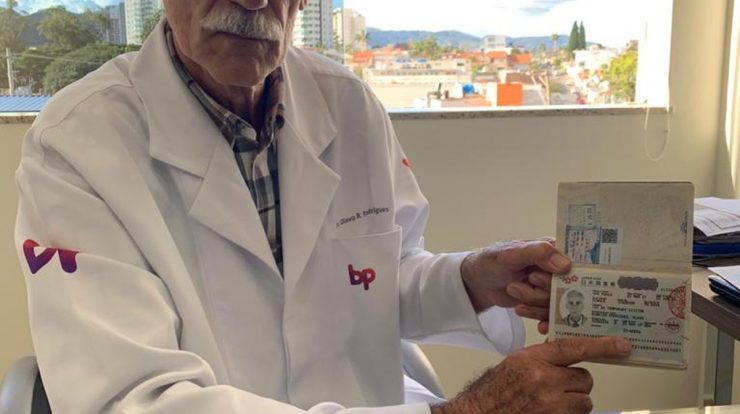

Dr. Olavo Ribeiro Nogueira is a volunteer for an NGO helping sick Brazilians who went to work in Japan to return to Brazil – Photo: Olafo Ribeiro Nogueira / Personal Archive

Despite all the hurdles, he embarked on another journey this year and arrived in Brazil in early April and brought in three patients. Given the global health situation, the trip was only possible this time because the doctor obtained a humanitarian visa to cross the world on another mission in these 47 years that he was practicing medicine.

The first pandemic case arrived in late 2020, but the doctor’s visa was suspended by the Japanese government due to the epidemic. Then a race against time began.

The doctor says he tried to get a visa in November and December but failed. In January, he tried again, but with the arrival of the second wave in Brazil and the emergence of a new strain of the new Corona virus in Manaus, Japan imposed further restrictions on the entry of foreigners, especially Brazilians, Africans and residents of the United Kingdom.

In February, the second patient appeared. She asked to speak to the São Paulo consul. The Brazilian government in Japan, Ambassador, submitted a request to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Ministry of Japan has authorized the Japanese Consul in Sao Paulo to provide a visa for me and the nurse accompanying me, ”explains Rodrigues.

He adds that he was granted a humanitarian visa, which is granted on an exceptional basis to perform the humanitarian mission of saving a vulnerable person. The visa was granted on March 22, two days before the doctor and nurse left.

A doctor at a meeting to bring patients from Japan to Brazil. Photo: personal archive

The doctor’s work begins long before boarding the plane. Still in Brazil, he remains in contact with the Japanese medical team who treats the patient and assesses each patient’s condition. Before traveling, make sure all transportation logistics are already settled. “I always count on the support of family members at this point and request a place in the hospital in the city where the patient lives and an ambulance for transportation. For example, the Paraná government, since it is an interstate transportation, sent an air taxi, which is a small plane with the ICU on Free board by SUS. ”

Olafo Ribeiro finishes his job upon arrival in Brazil and hands the patient over to the ambulance doctors who will take them to their home cities.

The job of the doctor is not easy at all. In addition to analyzing the patient’s condition in Brazil, and visiting and equipping him in Japan, he still faces a journey that can last up to 32 hours upon his return, on a scale of up to six hours, with continuous assistance.

Olafo Ribeiro’s work began in 2005 when he responded to a request from a family in Mogi das Cruzes to accompany their son in Japan. The boy’s condition was serious and he needed a heart transplant. “For cultural and religious reasons, organ donation is minimal in Japan.”

He hasn’t stopped since. For 15 years, he was a part of an NGO service to support Brazilian workers in Japan (Sabja) and for his work he received airline tickets, hotel accommodations, food, and transportation throughout Japan.

“We are taken on visits to Japanese hospitals and have clinical and surgical discussions about the risks and benefits of moving to Brazil, and we have received support from diplomatic authorities, our consulates and our embassy in Japan are our partners in these humanitarian missions. When I need to transport two or three patients at once, I take nurses.” They are paid for the work done. ”

With a lot of time on the job, Olafo Ribeiro says he is satisfied with the results achieved.

“In those years, I actually carried out or coordinated the transportation of 33 patients and only had one death in hospital in Japan. So I am aware of the duty that was done.”

Dr. Olafo Ribeiro, from Mugi das Cruzes, has brought patients from Japan to Brazil voluntarily for 16 years – Photo: Personal Archive

Reginaldo Oshima, 43, was one of the patients who returned with the doctor in April. He worked in an industry in Japan for 25 years, producing motorcycle parts.

Rosana Oshima Ribeiro de Mendonca, 45, is Reginaldo’s sister and says he has throat cancer and has been disappointed by Japanese doctors. “They said they really did everything, by radio and chemotherapy, and they wanted to take him to a place for treatment to relieve the pain,” Rosanna says.

Therefore, the family decided to bring Oshima to Brazil in the hope of a new evaluation and continued treatment. She says that without the help of a doctor from Mugi das Cruzes, she would not be able to bring her brother to São José do Rio Preto where the family resides. I already lived in Japan and tried to search, but they wouldn’t let me go without a doctor accompanying them on the trip. We will not be able to appoint a doctor to do that. ”

Rosana explains that Olafo Rodriguez went to the hospital where her brother was and took care of the papers for the patient’s release. “Dr. Olafo is a blessing and his role was essential for my brother’s return. There was a time when we lost hope and thought we wouldn’t be able to bring him back. But my brother is home now.”

Dr. Olavo Ribeiro Rodriguez’s patients had to wait a few more days for him. Upon arriving in the country at the end of March, he had to comply with a series of protocols for his final entry on Japanese soil due to Covid-19.

A doctor and nurse performed a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at a Japanese airport. Since the test was negative, they were taken by bus to a hotel in the airport complex where they stayed for three days.

“We received three meals and were unable to leave the hotel room. It opens the door to pick up the food left on the floor. You cannot exit in the lane that the security guard is observing. After three days of isolation, they sent a saliva collection kit for a new test. You receive a call in the room telling you the result if it is negative, you can enter, but if it is positive, they will take you to the hospital where you are staying for 14 days.

In the case of the doctor and the nurse, the test was negative. They also had to sign a term obliging them not to use transportation, be it a bus, train, plane or boat, and that the displacement would only be done by car. Finally, they were able to start taking care of patients, but they were always being monitored by the Japanese government with two apps.

The doctor says that in ordering what I needed daily to send out a questionnaire at 2 pm to answer yes or no if I had a fever, cough and sore throat. The answer went to the Coronavirus Emergency Center.

Another application is georeferencing to know where you are going in the country. It shows in real time the itinerary, the number of times they left the hotel to go to the hospital, where they stayed. If the Covid case appears in the next week on the route that I took, they will discover that I passed the disease In this way, they will be able to prevent passengers or foreigners from polluting the Japanese people. ”

The logistics for the doctor’s work are superb and involve many members in Japan, and Olafo Ribeiro’s work is still starting in Brazil. It starts with a letter from the consulate or embassy. Then he called the hospital to speak with the Japanese doctor who takes care of the patient, and then with the patient’s family to find out the reason for his desire to return. ”

He also receives a report from Japanese doctors to understand the types of equipment that he will need to bring from Brazil to bring back the patient, for example, cardiac endoscopes, oximeter, drug infusion pumps, excretory pumps, delayed feeding and collection probes, vasoactive drugs, pacemakers, etc.

All work can be done because the doctor speaks Japanese and English. Olafo Ribeiro’s wife was born in Brazil, but she is the daughter of Japanese. He learned the language with his wife’s family and in 1989 expanded his knowledge when he specialized in thoracic surgery and trained in a hospital in Japan.

“In Muji, nearly 50% of my patients are Japanese and grandchildren. I am always invited to attend Japanese language elders and this makes it possible for me not to forget the language,” he says.

The doctor explains that there are three consulates in Japan in Japan: one in Nagoya, one in Hamamatsu, and one in Tokyo. “Everyone has a record of Brazilians in these regions. The patient is appealing to the Brazilian consulate within his jurisdiction, which contacts me. Nagoya is the most contacted and where more Brazilians work. There is also an NGO, The Assistance Service for Brazilian Workers in Japan (Sabja) that helps In this process, it has been operating for 25 years in Japan and was created when the immigration and creation of the Brazilian community began there.

In Japan, it takes seven to eight days to prepare the patient. A job that is also helped by Japanese doctors and nurses treating patients.

Olafo Ribeiro does this in every city where patients are. “With everything ready, ambulances take patients to the airport and everyone arrives together at the boarding gate and we get on board. Never in economy class because of the space. You have to go to the executive with a reclining chair. If you need to, set up a unit.” Small Intensive Care On Board. ”

The cost of transporting a patient from Japan to Brazil ranges from R $ 28,000 to R $ 150,000 on average, according to the doctor. He points out that airlines do not allow patients in serious or very dangerous condition on domestic or international commercial flights without medical assistance, “It will depend on the airline, the capacity of the plane and the time of year, all this makes the cost variable. With the epidemic, there are a lot of empty seats.” The company is lowering the price. ”

The number of seats required varies according to the patient’s condition. “There is a situation where it is necessary to transport the patient on a special stretcher. Then it is necessary to remove six to eight seats and this stretcher is fixed to the ground at the end of the plane. You need to wear three belts for take-off and landing and to be safe in the event of turbulence.”

The doctor explains that the cost of the operation is paid by the patient’s family, Sabja, the Brazilian diplomatic authority, and the Japanese authority through the assistance provided by the government to the patient.