- Kimya Shakouhi

- BBC Future

attributed to him, Scientific

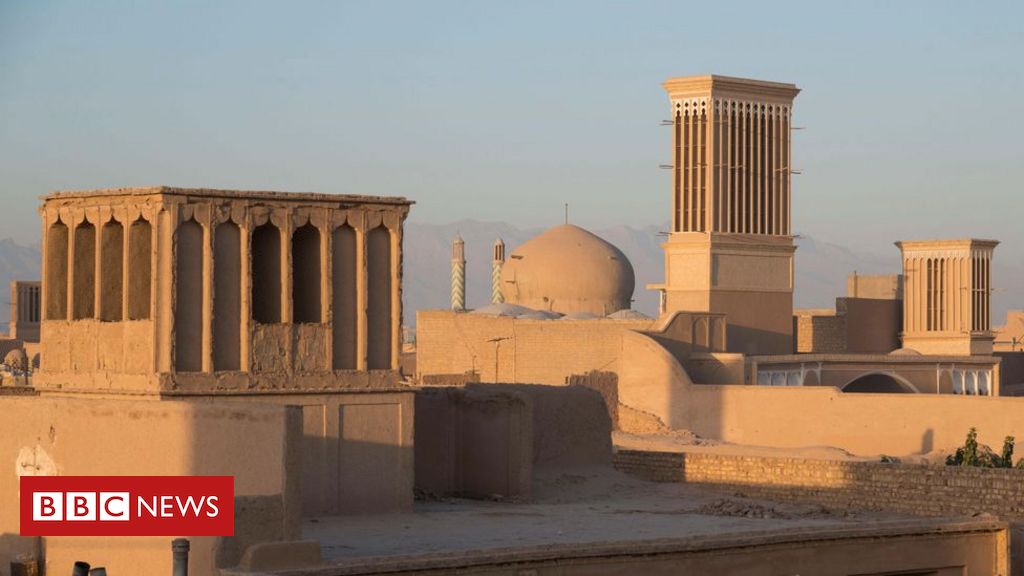

It is said that Yazd has more winds than any other city in the world.

From ancient Egypt to the Persian Empire, an ingenious method of capturing and directing the wind has been refreshing people for thousands of years. In the search for emission-free cooling, the “wind catcher” may come to our aid once again.

The city of Yazd, located in the desert of central Iran, has long been a center of creativity. Yazd is home to one of the wonders of ancient engineering – a system that includes an underground cooling structure called a yakhchal, an underground irrigation system called qanats, and even a messaging network called pirradazis, established more than 2,000 years before the US Postal Service.

Among the ancient techniques of Yazd is the wind trap, or badgir, in Persian.

These magnificent structures are commonly found on the roofs of Yazd. Most often they are rectangular towers, but they are also found in round, square, octagonal, and other ornate shapes.

Yazd is said to be the city with the largest number of wind pickups in the world. It may have originated in ancient Egypt, but in Yazd, the wind trap soon proved indispensable, making life possible in that hot, barren part of the Iranian plateau.

While many of the desert city’s winds are deserted, its structures are now drawing the attention of academics, architects and engineers to study the role they can play in keeping us calm in a rapidly warming world.

Since wind trucks do not need electricity to operate, they are a cheap, environmentally friendly method of cooling. With conventional mechanical air conditioning already accounting for a fifth of the world’s total electricity consumption, outdated alternatives such as wind traps are becoming an increasingly attractive option.

There are two main forces that push air through structures: ingress of wind and change in air force depending on temperature – warm air tends to rise above cold air, which is denser.

First, when air is captured by opening the wind sensor, it is directed downward into the building, causing any debris or sand to be deposited at the foot of the tower. The air then flows throughout the entire interior of the building, sometimes over aquifers to improve cooling. Finally, the heated air will rise and leave the building through a tower or other opening, with the help of pressure inside the building.

attributed to him, Scientific

The towers’ openings face the wind, directing it and distributing it downward into the buildings.

Tower shape and other factors – such as the layout of the house, the direction the tower faces, the number of openings, the configuration of the internal fixed vane, ducts, and height – are all properly selected to maximize tower capacity. Wind channel below the building.

The story of using wind to cool buildings began around the same time that people began to live in the environment of hot deserts.

One of the first wind-capturing technologies dates back 3,300 years ago, in Egypt, according to researchers Chris Soilberg and Julie Rich, from Webber State University in Utah, in the United States. In this system, the buildings had thick walls, few windows facing the sun, air intake vents in the main wind direction, and an exhaust vent on the other side – known in Arabic as the Malqaf geometry.

But there are those who argue that the wind sensor was invented in Iran itself.

In any case, wind pickups have spread across the Middle East and North Africa. Variations of Iranian wind producers can be found with local names, such as Barjeel Qatar and Bahrain, Egyptian Malqaf, Mung Pakistan and many others, according to Fatima Gomizadeh of Malaysia University of Technology and colleagues.

It is believed that the Persian civilization added structural variations to allow for better cooling, such as incorporating it with existing irrigation systems to help cool the air before it was released throughout the house.

In Yazd’s hot and dry climate, these structures became increasingly popular, so that the city became an oasis of towering ornate towers in search of the desert winds. Yazd is a historic city that was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2017 – in part because of the large number of wind trucks.

In addition to fulfilling the functional purpose of cooling homes, the towers also had a strong cultural significance. Wind pickups are part of the landscape in Yazd, as is the fiery temple of Zoroaster and the Tower of Silence.

attributed to him, Scientific

After a long time without use, the conservation status of many Iranian wind sensors is no longer good, but some researchers want to restore them and put them back in business.

Then there is the wind pickup at the Jardim de Dowlat Abad, which is believed to be the tallest in the world (at 33 metres) and one of the few still operating. Housed in an octagonal building, it faces a fountain and lake that stretches along rows of pine trees.

Possible rebirth?

With the cooling effectiveness provided by these zero-emissions winds, some researchers argue that they deserve a resurgence.

Researcher Parkham Khairkhan Sanghdeh has carefully studied the scientific application and local culture of wind traps in contemporary architecture at Ilam University in Iran, where many people have abandoned traditional wind sensors.

Instead, mechanical refrigeration systems such as conventional air conditioning units are used. These alternative systems are often powered by fossil fuels and use refrigerants that act as potent greenhouse gases when released into the atmosphere.

The emergence of modern cooling technologies has long been blamed for the decline of traditional styles in Iran, Iranian architectural historian Elizabeth Beasley wrote in 1977.

Without constant maintenance, the hostile climate of the Iranian plateau has eroded many structures, from windbreaks to ice storage houses. Jerkhah Senjdeh also notes that the abandonment of wind trucks was partly due to the tendency of the public to adopt technologies from the West.

“There has to be a change in the cultural perspective of using these technologies,” says the researcher. “People need to look into the past and understand why energy conservation is so important,” starting with the recognition of cultural history and the importance of the power of conservation.”

Khairkhah Sangdah hopes that Iran’s wind traps will be modernized to provide energy-efficient cooling for existing buildings. But he faces many obstacles to this work, such as the current international tensions, the COVID-19 pandemic and the current water shortage. “The situation is very bad in Iran,” he added [as pessoas] It takes one day at a time.”

attributed to him, Scientific

When architects sought passive methods of cooling, Iranian wind sensors inspired modern designs in Europe, the United States, and other parts of the world.

Non-fossil fuel cooling methods and systems, such as windbreaks, may deserve a resurgence, but to the surprise of many, they are already in place—albeit not as large as the Iranians—in many Western countries.

In the UK, around 7,000 different types of wind sensors were installed in public buildings between 1979 and 1994. They can be seen in buildings such as the Royal Chelsea Hospital in London and in supermarkets in Manchester.

These modern wind streams bear little resemblance to Iranian tower-shaped structures. In a three-storey building on a busy street in North London, small ventilation towers painted hot pink provide passive ventilation. Perched on top of a shopping center in Dartford, UK, the conical ventilator towers rotate to catch the breeze with the help of a spoiler that keeps the tower facing the wind.

The United States has also enthusiastically embraced designs inspired by the wind. One example is the visitor center at Zion National Park in southern Utah.

The park is located on a high desert plateau, with a similar climate and topography to Yazd, and the use of passive cooling techniques such as wind capture has almost completely eliminated the need for mechanical air conditioning. The scientists recorded a temperature difference of 16 degrees Celsius between the outside and inside of the visitor center, despite many people regularly passing through the site.

As the search for sustainable solutions to global warming deepens, more opportunities arise that favor building wind sensors. In Palermo, Italy, researchers found that prevailing weather and wind conditions make the city a hotspot for an Iranian version of the wind truck.

In October, the wind sensor was prominently displayed at the Expo Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, as part of a network of conical constructions at the Austrian Pavilion. The Austrian architecture firm Querkraft was inspired by the Barjeel to create it – the Arabic version of the wind sensor.

While researchers such as Jerkhah Sangde argue that a wind truck has a lot to offer to cool homes without using fossil fuels, this innovative technology has already moved to other parts of the world — more than one might imagine. The next time you find a tall vent tower on top of a supermarket, building, or school, look carefully. You may look at the heritage of the wonderful wind traps in Iran.

You have seen our new videos on Youtube? Subscribe to our channel!