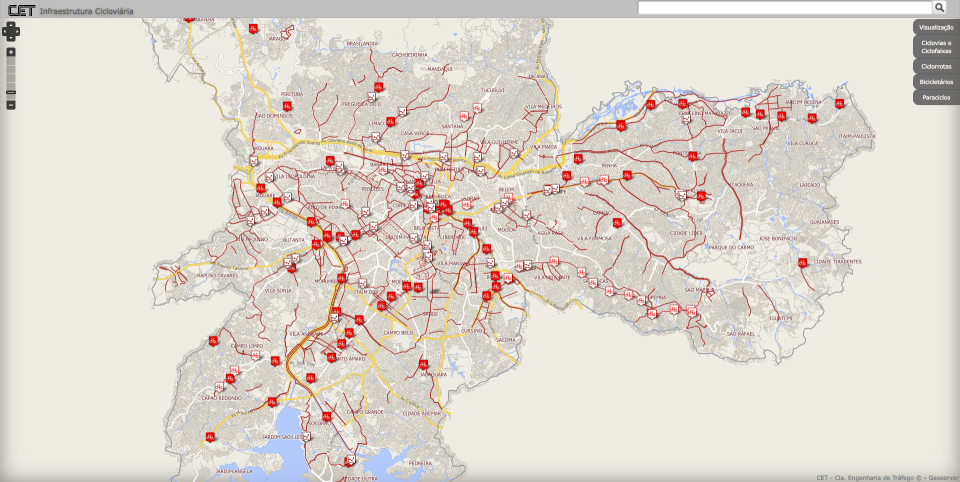

At the age of 21, university student Les Levski was born as a cyclist when the city already had 380 km of bike lanes and exclusive lanes, which allowed her to begin at the age of 15 to travel the 7 km separating her home, in Villa Sonia, from the school in Alto de Pineros. He comments, “I did not dare to share the ways that share spaces with cars.” “I’ve stopped going places because they don’t have a bike lane or something like that, because it’s more dangerous, as well as potholed and poorly lit streets; if it weren’t for all that structure, it would surely take longer to adopt the bike as a mode of transportation, or I might not have been able to do that.”

The Lis reflects part of the reality of cycle paths, which, as revealed in the first report of this series, although necessary and a sign of progress in the assessment of specialists, ends with neglecting the integration of the parties, which historically makes the greater use of the bicycle as a means of transportation for economic issues. (Read the second report here)

Studies by the Centro de Estudos das Metrópoles (CEM), which is affiliated with the University of the South Pacific’s School of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, show that the income of residents within 300 meters of bike lanes and lanes is 43% higher than the São Paulo city average. In areas around shared bike stations, this difference increases to 223% greater than the average.

“A notable discrepancy is the lack of bike lanes and lanes in areas where a large portion of the population does not own a car,” assess the authors of the note, who claim that blacks, in addition to lower incomes, occupy locations in the city that provide less access to public transportation, Public transport functions, including the bicycle network.

Living within 500 meters of a bike path increases the chance of using a bike as transportation in São Paulo by 154%, according to a study conducted by University of the South Pacific researchers with the University of Melbourne, Australia. The research also assessed that traveling on rails within a radius of up to 1,500 meters increases the chance of using a bike by 107%.

Six years after starting bike commuting, Liss now has a license to drive the family car, but she continues to prioritize the bike, and says she better understands the dangers of lane sharing. “There are a lot of reckless drivers, but I also see a lot to watch out for; if I had the idea of using the street before ‘because I’m a minor, I have the preference and you’re the one to deal with’, today I understand it’s a more complex issue.

Complexity is only dealt with, understood and addressed in depth when discussed by society – a process that began about a decade ago and continues, in Renata Falzoni’s view. “Today there is a measurable cultural legacy; the community has come to see that where there are bike lanes, there are no deaths, the residents approve of the initiative,” he advocates.

The latest study by Cebrap (Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning) indicates that more than 80% of the population of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro agree that public authorities should invest more in a transportation system that prioritizes cycling and walking after the pandemic and conducive to creating bike lanes and lanes New in town.

“It is sad that we faced the dilemma of making a mistake or not, but that is what we live in in Brazil; in any case, there is no doubt that the past ten years, even between failures and mistakes, progress in this field has been tremendous,” concludes Walter Caldana. It was excellent and necessary and if it had not happened it would have been a disaster.”

“Friendly zombie guru. Avid pop culture scholar. Freelance travel geek. Wannabe troublemaker. Coffee specialist.”