- Daniel Bardot

- Special Envoy to Caracas

attributed to him, Environmental Protection Agency

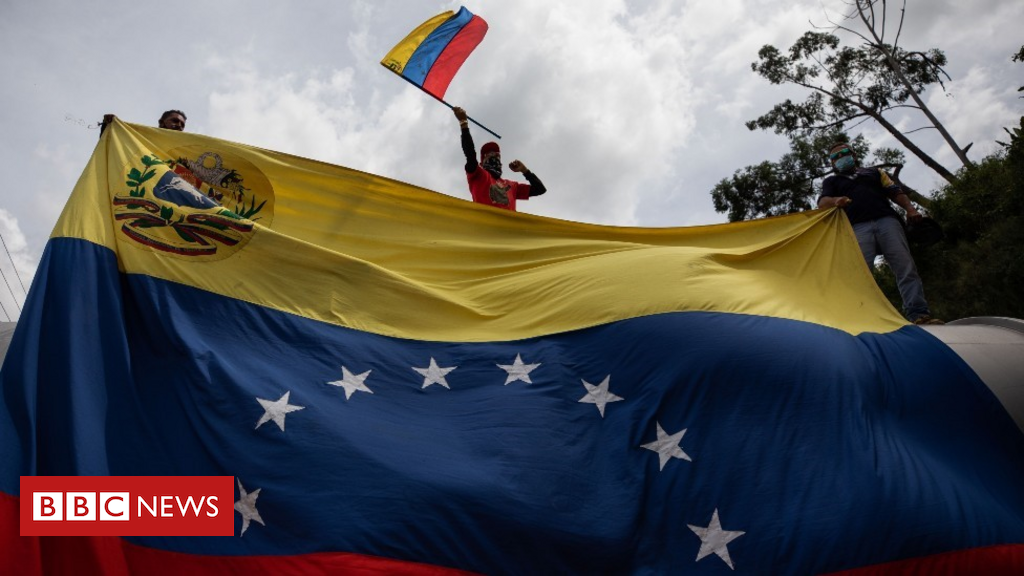

Polls will reveal how Venezuela – and who will lead the country – is heading toward a political transition

Elections, after years of boycott by the opposition, are being held again in Venezuela on Sunday (21/11).

And in the “Great Elections” 3,082 positions will be elected: 23 governors, 335 mayors and hundreds of seats on local councils.

Elections in which Chavismo faces a wide section of the opposition has mostly not recognized the electoral system in the 2018 presidential election or in the 2020 legislative elections.

This time, there will also be impartial election observation. And international interest in knowing whether the government of Nicolas Maduro is able to ensure democratic competition.

“This Sunday, we will bring good news to the world,” the Venezuelan president said.

Venezuelans go to the polls at a rare moment for the country: after decades of deep polarization, politics is no longer one of the people’s main concerns, and de facto dollarization and economic openness have made it possible to mitigate the crisis, revitalize production and, in part. Mitigating urgent needs.

Added to this is the fact that a fifth of the 21 million Venezuelans registered to vote will not be able to because they are abroad, having traveled to escape the crisis.

Therefore, one of the keys to these regional and municipal governments is whether, and to what extent, the small participation of 30% of the people will be exceeded in the 2020 legislative elections, which Chavismo won without real competition.

And this Sunday, despite the opposition’s participation, Chavismo will likely reign again.

“Of course, due to the abstentions and inequality in the dispute, the main political force in the country will be chavism,” says policy advisor Colette Capriles.

“But that is why this election will serve as a precursor, and as a measure of strength, within each side.”

Both the Chavismo and the opposition are divided, influenced by a series of exclusions, interventions and taboos that for many do not guarantee a genuine democratic process. On both sides, there are dozens of candidates frustrated by court decisions.

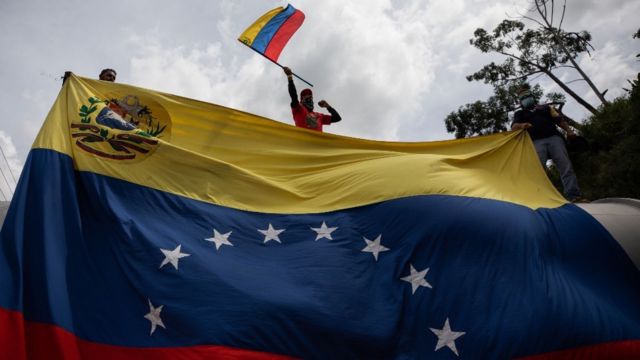

However, the renewal of mayors in the National Electoral Council (CNE) in May, the monitoring of international elections and some of the commitments made in the negotiation process in Mexico give, for some, the idea that the democratic transition has tentatively begun.

“We have to rebuild our institutions,” says Enrique Marquez, opposition politician and dean of the CNE, the body that organizes elections and which has been made up of members appointed by Chavismo for years.

“But for that we have to go little by little, like someone is reorganizing a house, little by little (…) Now, at least we can say with absolute confidence that in the electoral sphere, after many checks and updates, he will have a secure vote And another secret.”

attributed to him, Environmental Protection Agency

Venezuela has a “huge election” with the opposition to the dispute

Why are these choices different?

The elections will witness a monitoring mission from the European Union, another from the United Nations, and one from the Carter Center, which are bodies specialized in electoral operations.

Since the 2015 legislative elections, in which the opposition won by a large margin, the monitoring of impartial international entities has shrunk until they have disappeared.

If in 2020 these election commissions justified their absence with a “lack of democratic conditions,” the opposition’s argument is now, at least in principle, more or less satisfied.

Although dozens of politicians have been excluded, banned, or even imprisoned, the renewal of the CNE has been seen as an unprecedented development in recent decades.

attributed to him, Environmental Protection Agency

The renewal of the CNE in Venezuela is seen as an unprecedented development in recent decades.

Since 2006, the President of the National Electoral Council has been Tibisay Lucena, the current Minister of Maduro’s government. The mayors’ representation was always called into question by the opposition, which had only one out of five representatives in the Electoral College.

“US sanctions have forced the government to capitulate in several areas, and this renewal of the English National Council is one of them,” says Louis Vicente Leon, an analyst and researcher.

Today, the opposition has two of the five National Assembly presidents, a difference that has resulted in, among other guarantees, “we will have strong witness accreditation systems.”

The dilemma of the opposition

Another big difference between this election and the previous one is that the opposition, which has not recognized Maduro as president since 2018, is back in the electoral game.

It is not the same opposition as before – there are new parties and new candidates – nor is the entire opposition, because there are still groups calling for abstinence, such as the Popular Will faction led by Juan Guaido, which guarantees that “regions and municipalities are not the solution to conflicts”.

However, Chavismo’s opponents on Sunday have someone to vote for, if he dares.

“In opposition to Chavismo so far, the branch that promised an uprising or a sudden change of government has had more power,” says Colette Capriles. “But now the immediate availability of support for the sudden changes seems to have diminished.”

attributed to him, Environmental Protection Agency

The opposition does not promise the end of the Maduro government, nor does it base its case on resentment against Chavismo.

He explains that “the personal suffering was so great that it forced people to sever their ties to politics, which although it affects the mechanisms of solidarity, in turn allows for a certain renewal of the party structure of the opposition.”

This time, the opposition is not promising to end the Maduro government, nor is it building its case on discontent against Chavismo. “I hope that no one comes with an atmosphere of victory,” Gustavo Duque, the opposition candidate for mayor of Caracas, said in his closing campaign.

Experts see the election as a referendum by the radical wing of the opposition led by Guaido, who is seen by dozens of countries as Venezuela’s interim president and whose leadership is increasingly being questioned.

“The engaged opposition seeks to establish itself as the real opposition, who can really bring about changes in the country,” says Luis Vicente Leon.

attributed to him, Environmental Protection Agency

Although neither a candidate nor a spokesperson for the opposition, Henrique Capriles was one of the promoters related to the return to the opposition elections

But at the same time, he remains skeptical: “The problem is that those who participated fail to unite, and they will split into two or three very different coalitions, and this will prevent a clear map of the opposition forces after the elections.”

There are approximately 40 terminals on an electronic card. Four different opposition forces will claim their emergence in one way or another depending on their results.

This will be central to Guaido’s leadership, to the negotiation process with Maduro, in Mexico, which should resume in January, and to the next elections (the presidential election will be in 2024, and there is a possibility, albeit remote, to recall the referendum in 2022).

Venezuela is trying to enter a political transition in the midst of the economic transformation that has already begun. It seems clear that the first, if it happened, would be much slower than the second.

You have seen our new videos on Youtube? Subscribe to our channel!